|

One of the most eagerly anticipated events in the United States in the early days of December 1851 was the imminent arrival of Lajos Kossuth, the leader of Hungary's fight for independence against the Hapsburg dynasty during the great revolutionary years of 1848-49. The American public had much sympathy for the Hungarian cause. Abraham Lincoln, Congressional representative from Springfield, Illinois, presented a resolution of sympathy with the cause of Hungarian freedom to a mass meeting on September 12, 1849. President Zachary Taylor even sent an envoy, A. Dudley Mann, to Europe to ascertain the political situation as he was contemplating to recognize the revolutionary regime. However, by the time Mann arrived, it was too late; the Hapsburg forces, aided by a massive army dispatched by Czar Nicholas of Russia, were victorious.

Kossuth and several thousand others sought and found asylum in the neighboring Ottoman Empire. Following considerable diplomatic wrangling, Kossuth and a small group of exiles constituting his entourage were interned. The internment lasted until the arrival of the Mississippi, a warship dispatched by the United States government to convey Kossuth and his followers to the United States. On September 10, 1851, the Mississippi cast off with Kossuth and some fifty others aboard. As the vessel entered the western Mediterranean, Kossuth insisted on interrupting the journey to pay a quick visit to Great Britain. Accompanied by his family and a handful of retinue, he disembarked at Gibraltar. The Mississippi entered New York harbor on November 10th while Kossuth was touring England to enormous popular acclaim, all of which was faithfully reported in the American media.

A frenzied throng of over 100,000 headed by Mayor Ambrose Kingsland greeted Kossuth when he made his official entry into New York City. In the ensuing weeks, he attended numerous banquets, received individuals and delegations, and addressed various assemblages. He made a most favorable impression and the public's fascination with him - dubbed "Kossuth fever" - continued to rage unabated.

Kossuth's enormous appeal has been attributed to a variety of reasons. Perhaps the best summation has been advanced by long-time politician Galusha A. Grow: "Kossuth was worthy of all the honors that were heaped upon him. His handsome presence, the marble-like paleness of his complexion, caused by hardship while in prison, and the picturesqueness of his foreign dress, captivated the popular fancy; while, more than all, his wonderful eloquence and the fervor with which he pleaded his country's cause, left an influence upon the hears of those who heard him that nothing could destroy."

On the way to Washington, DC, the enthusiasm of the people was as tumultuous as that exhibited in New York. However, his reception at the White House was far more subdued, to say the least. Unlike Zachary Taylor, Millard Fillmore, who succeeded to the presidency on the death of Taylor, had no interest in Hungary nor was he inclined to make any promises of support. Fillmore insisted on adhering to America's traditional policy of "staying clear of foreign entanglements." Given the situation in those days, any form of aid, whether military or diplomatic, would have been extremely difficult, if not outright impossible, and certainly not beneficial whatsoever to the United States.

Determined not to abandon the struggle for the Hungarian cause, Kossuth toured most of the United States east of the Mississippi River to proclaim his mission. With the exception of the Deep South, the reception accorded was favorable. His visit to New England was particularly rewarding as many of the nation's foremost figures residing in this region spoke out in support. But popular enthusiasm didn't translate into tangible official help. A disappointed Kossuth left the United States on July 14, 1852, and took up residency in London, England.

While Kossuth didn't stay, memory of his visit lingered for decades. Year later many ordinary and distinguished Americans - among them Alexander K. McClure, Samuel Gridley Howe, George F. Hoar, and William Dean Howells - nostalgically recalled that the opportunity to see and hear Kossuth constituted a highlight of their lives and the deep and lasting impression he made upon them.

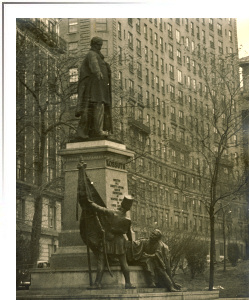

Today, statues, plaques and sundry other reminders throughout America attest to that historic tour. Perhaps the best known of the statues is the imposing creation of artist János Horvay on Riverside Drive near Columbia University. Kossuth has also been honored by the U.S. Post Office in the Champion of Freedom series of stamps. Today, statues, plaques and sundry other reminders throughout America attest to that historic tour. Perhaps the best known of the statues is the imposing creation of artist János Horvay on Riverside Drive near Columbia University. Kossuth has also been honored by the U.S. Post Office in the Champion of Freedom series of stamps.

Although Kossuth didn't settle in America, three of his sisters and their families did. Kossuth had four sisters: Zsuzsanna (Susanna), Lujza (Louise), Emilia (Emilia), and Karolina (Caroline). Zsuzsanna was a widow of Rudolf Meszlényi with two young daughters (Gizella and Ilona, nicknamed Ilka)) when the revolutionary tide swept over Europe. Lujza was the wife of József Ruttkay, and they had three sons: Lajos (Louis), Béla, and Gábor (Gabriel). Emilia was married to an ethnic Pole by the name of Zsigmond Zsulavszky (written as such in Hungarian) and they had four sons: Emil (Emil), László (Ladislas), Kázmér (Casimir), and Zsigmond (Sigismund). Karolina's husband was István Breznay, a physician.

When Kossuth took refuge in the Ottoman Empire, members of his family remained in Hungary. His wife and children were able to elude the Hapsburg authorities and join him in the Ottoman Empire. However, Zsuzsanna, Emilia, and Lujza and their families were not so fortunate. They, as well as Kossuth's aged mother, were placed under surveillance and subjected to incessant harassment. Because Karolina and her husband did not take an active role in the events of 1848-49 they were spared from these tribulations.

At last, thanks in large measure to the relentless efforts of Charles McCurdy, American diplomatic representative in Vienna, Zsuzsanna, Lujza, Emilia and their families along with Kossuth's mother were granted permission to leave the country. When József Ruttkay refused to emigrate, Lujza promptly divorced him. Kossuth's mother, already in precarious health, died in Brussels, Belgium.

On July 6, 1852, Emilia, her husband, and three of their sons - Emil, Casimir and Sigismund - boarded the steamer Humboldt at Southampton, England, for New York City, arriving on the 19th. Ladislas remained behind in Europe for a while to complete his studies. Lujza and her children made the trans-Atlantic voyage almost a year later; they arrived in New York on May 11, 1853, aboard the passenger vessel Hermann. The entire journey of the families was carefully observed by agents of the Hapsburg government who made frequent reports about their whereabouts and activities.

It was Kossuth's fervent hope that his sisters would settle on some bucolic farm in Iowa, where a number of Hungarian refugees had already established themselves. However, sisters emphatically declared that they had no intention whatsoever to live in a remote wilderness, preferring to domicile in New York.

To make matters easier for their new friends and neighbors, the Zsulavszky family began to write their name in a quasi-Americanized form: Zulavsky. They as well as members of the Ruttkay family began to use the English version of their given names. Since Béla, a popular male name harking back to the old pagan days, has no such equivalent and is rather similar to Bella, Béla Ruttkay became Albert Ruttkay. However, in the intimate family circle he was still called Béla, leading to understandable confusion among Americans. As a matter of fact, stories about "Mr. and Mrs. Bella Ruttkay" appeared sporadically in the press for decades.

Notwithstanding generous help from a number of prominent and well-to-do Americans - notably George Luther Stearns - the sisters struggled in the new homeland. To support themselves and their families, Lujza and Zsuzsanna opened a shop on Broadway selling "laces, silks and other articles of female apparel." In several of its issues - e.g. on September 27, 1853 - the New York Times urged its readers to patronize their shop: "While these ladies have a collection of articles selected with a degree of taste which cannot fail to commend them to favor, their characters, accomplishments, and conditions as strangers among us, entitle them to the aid of those whose sensibilities enable them to appreciate their situation. We solicit for them the attention and friendly consideration of the public." With Christmas fast approaching, the December 5, 1853, edition of the New York Times reminded its readers that "the stock of fine laces kept by Madame RUTTKAI, No. 769 Broadway, is well adapted for the selection of such articles, as will never fail to please the most fashionable and fastidious City lady."

Emilia set up a boarding house in Brooklyn. Serious marital problems with her husband, described in several memoirs as a rather frivolous and ill-tempered individual, culminated in divorce. He then faded from the scene, leaving Emilia alone to raise their four sons.

Zsuzsanna, already stricken with tuberculosis, died in 1854. Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, the outstanding pioneer reformer in many spheres, wrote a touching tribute to her entitled Memorial of Madame Susanne Kossuth Meszlenyi. The two little orphaned girls were then adopted by a lady from the wealthy and prominent Cruger family. Subsequently, when they grew up both returned to Hungary. Gizella died young, in 1865, like her mother a victim of tuberculosis. Ilka, however, survived her sister by many years, passing away in 1926.

Giving up shop keeping a few years, Lujza, a thoroughly cultured woman, established a private school for young ladies in Cornwall, just north of New York City. For several years ads for the school were a regular feature in the New York Times and other leading local papers. Commenting on the institution, the New York Times, May 23, 1859, wrote: "Mme. R. is a sister of KOSSUTH, and a lady of high accomplishments and most estimable character. . . . her school is spoken of in the highest terms by those best qualified, by opportunity and experience, to express a judgment in regard to it."

Even though Lujza and Emilia lived under very modest circumstances, they ensured a good education for their boys and their homes were always open to fellow exiles. Among the notable ones paying frequent calls on the sisters were Károly László, the Reverend Gedeon Ács, and Alexander Asboth, all of whom came to America aboard the Mississippi. Asboth occupied a particularly fond niche in the hearts of the Kossuth family. An engineer by education, he was an aide with the rank of lieutenant colonel on Kossuth's staff during the war, was at Kossuth's side when they crossed the border into the Ottoman Empire, and shared the entire Turkish internment with him.

Also among Emilia's circle of friends was the Reverend Samuel Longfellow, brother of the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, himself an ardent admirer of Kossuth. According to a retrospective article printed in the Brooklyn Eagle, Emilia maintained close contacts with Lola Montez, the legendary international courtesan and one-time mistress of King Ludwig of Bavaria, now a neighbor.

Within a few years after the passing of Zsuzsanna, Emilia also began to show the symptoms of the dreaded disease. She became so debilitated physically that even the simplest chores taxed her to complete exhaustion. Fortunately, a well-to-do and generous neighbor, Mrs. Richard Manning, took Emilia into her home and cared for her. It's here that she died on June 29, 1860. Her passing and funeral were covered by all the local newspapers. She was laid to rest in Brooklyn's sprawling Greenwood Cemetery in the presence of virtually the entire Hungarian colony of the city. Family intimate Alexander Asboth delivered the farewell address at the graveside. Within a few years after the passing of Zsuzsanna, Emilia also began to show the symptoms of the dreaded disease. She became so debilitated physically that even the simplest chores taxed her to complete exhaustion. Fortunately, a well-to-do and generous neighbor, Mrs. Richard Manning, took Emilia into her home and cared for her. It's here that she died on June 29, 1860. Her passing and funeral were covered by all the local newspapers. She was laid to rest in Brooklyn's sprawling Greenwood Cemetery in the presence of virtually the entire Hungarian colony of the city. Family intimate Alexander Asboth delivered the farewell address at the graveside.

Almost immediately after the death of their mother Emil and Ladislas left the United States to join the Hungarian Legion in Italy where tumultuous and profound political currents were reshaping the map of Europe.

In 1859 the Kingdom of Sardinia in alliance with Napoleon III's France fought a brief but bloody war against the Hapsburg Empire in northern Italy. The outcome of the war was a grave disappointment to Italian patriots as well as Hungarian exiles, but the invasion of the Kingdom of Naples by the legendary Giuseppe Garibaldi in the spring of 1860 revived their spirits. Both events drew a large contingent of Hungarian expatriates to Italy. During Garibaldi's campaign in Sicily, the Hungarian volunteers formed a unit of their own, and it was this Legion that the Zulavsky brothers enrolled in.

After the decisive defeat of the Neapolitans at the battle of the Volturno, October 2 -3, 1860, the Hungarian Legion was retained in the service of the newly formed Kingdom of Italy. Ladislas, the most militarily talented of the brothers, became an officer on the staff of Geneal Antal Vetter, commander of the Legion at the time. The highest rank attained by Emil was corporal. The brothers remained with the Legion until late1862.

Their return to the United States via England aboard the Glasgow was reported by several newspapers, e.g. the New York Times, December 29, 1862, and the Lowell Daily Citizen and News, January 12, 1863. They immediately offered their services to the Union cause, joining their brothers Casimir and Sigismund and cousin Albert Ruttkay in the fight against the Confederacy.

Albert Ruttkay began his military career as captain with the 4th Regiment US Colored Heavy Artillery Infantry. Transferring to the 1st Florida Cavalry through promotion, he became the regiment's major.

Contrary to claims in certain writings, neither of the other two Ruttkay brothers, Louis and Gabriel, served in the Civil War. Louis' health was far from robust and Gabriel was only 14 years old when Fort Sumter was fired upon. Károly Kertbeny's massive 1864 tabulation of Hungarians abroad has both of them as civil servants employed at the customs house in New York City. Louis, who graduated from Union college in 1857, obtained a law degree from Columbia University in 1865. His graduation from both institution was noted in the newspapers, and he is listed in Columbia's alumni directory.

Ladislas Zulavsky's military acumen was quickly recognized and appreciated; he became colonel of the 82nd Regiment U.S. Colored Infantry, originally organized as the 10th Regiment Infantry Corps d'Afrique. Emil and Sigismund also served in this regiment; Emil rising to the rank of first-lieutenant while Sigismund was a second lieutenant. Sadly, Sigismund's tenure was brief; he died on September 16, 1863 at Port Hudson, Louisiana, a victim of typhoid fever, aged 19 years. He was buried next to his mother in Greenwood Cemetery.

For a substantial period in the latter stages of the war the 82nd U.S. Colored Infantry and the 1st Florida Cavalry were assigned to the District of West Florida. Their commanding officer was none other than old family friend Alexander Asboth, holding the rank of brigadier-general.

Florida wasn't a major theatre of the war; the primary mission of Asboth and his troopers was to scatter bands of Confederate regulars and irregulars and to wreak havoc on enemy supply lines. They pursued these objectives relentlessly and effectively, raiding far and wide. Several Hungarians besides the Kossuth nephews served under Asboth. According to William Watson Davis' monumental and influential The Civil War and Reconstruction in Florida, dating from 1913, Asboth and "his fellow Hungarians were hated, dreaded, and condemned by the country people of that section on the triple charge of being "furreners," Yankees, and nigger lovers."

In the last week of September 1864 an expedition of over one thousand soldiers with Asboth himself at the head and Ladislas Zulavsky second-in-command set out against Marianna, the seat of Jackson County. There, they were met by a hastily assembled force of locals. Due to overwhelming numbers and superior firepower, the Federals swept through the town, easily dispersing the defenders. During the brief but intense fighting Asboth was severely wounded in the arm and face, incapacitating him. Command thereupon devolved upon Ladislas, who guided the expedition safely back to base. Official reports praised Ladislas' conduct and leadership. Albert Ruttkay also received favorable citation for gallantry.

Ladislas and Emil were mustered out with their regiment on September 10, 1866. In the waning days of the war Albert Ruttkay was an aide-de-camp on the staff of General Nathaniel Banks. Because of their service with the US Colored Troops, the names of Albert Ruttkay and the Zulavsky brothers - Ladislas, Emil and Sigismund - are inscribed on the African-American Civil War Memorial.

Casimir's career as a Union soldier took a very different path. George Luther Stearns, long involved in the Kansas conflict between pro- and anti-slavery elements which included outright support for John Brown, had excellent connections in that troubled land and used his influence to secure a position for Casimir. He was mustered in July 24, 1861, as first-lieutenant and adjutant of the 3rd Kansas Infantry. In April of the following year, the 3rd, 4th and a portion of the 5th Kansas Infantry regiments were consolidated to form the 10th Kansas Infantry. Casimir retained his rank in this regiment and acted as adjutant until June 1, 1862. Letters and diaries by several comrades describe him as a pleasant young man and an accomplished piano player.

Calling Casimir implicitly or explicitly the black sheep of the family, a number of Hungarian and American writings claim that while he was in the Union army he became involved with dubious characters and was party to certain criminal acts. One of the books which dwells in some detail about Casimir's unsavory activities is Frank Preston Stearns' biography of his famous uncle The Life and Public Works of George Luther Stearns, published in 1907. According to this work, young Casimir wasn't above skimming and stealing while in the elder Stearns' employ. However, despite Casimir's irresponsible and unrepentant behavior, the elder Stearns remained kind and generous toward him.

This particular book, like other writings encountered, is extremely vague about the specifics of the grave crimes committed by Casimir, giving rise to the speculation that they were perhaps nothing more than exaggerations blown out of proportion.

In 2003 I was conducted by Howard Mann who was researching the 10th Kansas Infantry because an ancestor served in the regiment. As such, he was very much interested in the Casimir Zulavsky story. We exchanged the information we each had on Casimir in our possession at the time. Howard told me that sifting through massive piles of official documents, newspaper stories, and various other sources, did not yield any supporting evidence of crimes by Casimir.

Since 2003 there has been a veritable explosion in the availability of historical information and tremendous advances in tools to sift through vast mounds of printed and handwritten papers reposing in sundry archives. Therefore, not surprisingly perhaps, as I delved into an array of databases to double-check various facts connected with this particular treatise, two newspaper articles popped up which confirm Casimir's participation in criminal activities.

The first, from the March 31, 1863, edition of The Smoky Hill and Republican Union, of Junction City, Kansas, reports on Casimir's capture and arrest by Deputy Sheriff Soule in St. Joseph. The second, published in the same paper on May 23rd, covers the legal proceedings against Casimir for stealing knives from the Express Office and money from a certain Mr. Haskell. Having been found guilty on both charges, he was sentenced to 18 months in the State Penitentiary for the first offense and to three years on the second indictment.

At the end of the war large numbers of soldiers and sailors, Union as well as Confederate, formed a multitude of veterans' organizations. Especially popular with Northern servicemen were the GAR (Grand Army of the Republic) and MOLLUS (Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States). Hungarian veterans of the conflict were well represented in these type of associations. For example, Major-General Julius Stahel, winner of the Congressional Medal of Honor, was a member of MOLLUS as well as GAR as was Frederick Knefler, colonel of the 79th Indiana infantry and brigadier-general by brevet. Colonel Joseph Vandor, 7th Wisconsin Infantry, served as Judge-Advocate for the GAR's Department of California in 1871. Other Hungarians frequently cited in the news in connection with veterans' groups include Charles Semsey, Theodore Korony, Charles Vidor, and Eugene Kozlay. However, the only Kossuth nephew affiliated with a veterans' organization was Ladislas Zulavsky; he was a member of MOLLUS, New York Commandery, Insignia #: 01167.

Following his demobilization, Albert Ruttkay became involved in the cotton trade and soon his business, A. Rutkay & Co., was active in Houston, Galveston, and Dallas, Texas. That he was esteemed and respected by his associates and fellow businessmen can be ascertained by the important posts he was entrusted with, including a director of the Houston Cotton Exchange and Board of Trade. Advertisements for his firm were a regular feature in Galveston newspapers, such as Flake's Bulletin and the Galveston Daily News.

Interestingly enough, one of principal founders of the Galveston Cotton Exchange was also a Hungarian veteran of the Civil War but on the Confederate side, Charles Vidor, remembered nowadays as the grandfather of famed film director King Vidor. Since Ruttkay and Vidor both maintained offices in Galveston's Strand Street, were in the same line of business, participated in similar civic affairs, and enjoyed the same cultural venues, their paths must have crossed often.

Albert Ruttkay met his wife, Laura Wiley, in Plainfield, New Jersey, while visiting his mother there. Laura was the youngest daughter of Alexander Wiley, a principal of the firm of Morgan & Wiley, New York City. Their first child, Albert Kossuth Ruttkay, died in August of 1874 while still an infant. Another one also died in infancy, but three others survived: Louis, Paul and Gabriel.

Louis, Albert's older brother, married Delia, the only daughter of Captain John Collins and nice of E. K. Collins, of the Collins Line of steamers. They eventually moved to Des Moines, Iowa. A prominent attorney in the city, he was forced to abandon the legal profession in favor of real estate and finance as his health continued to decline. He often spoke and wrote about his famous uncle, now residing in Italy. Louis and Delia had four children, two boys and two girls. Apparently the children inherited their father's weak constitution; in 1894 only one was still among the living, namely Anne C. Ruttkay. Louis himself died in 1881 and his widow in 1900.

After Casimir Zulavsky's difficulties in Kansas had been resolved, he moved to Texas and joined Albert Ruttkay's business. For several days early in January 1866 the Galveston papers, e.g. Flake's Bulletin, carried announcements that S. A. Masters was no longer a partner in A. Ruttkay & Co., that role now being filled by Casimir. Advertisements for the firm of appearing in the newspapers displayed both of their names in the boxes: Albert Ruttkay in the upper left and C. B. Zulavsky in the upper right.

This business arrangement lasted until May of the following year when it's termination was publicized in a terse notice in the local papers. Flake's Bulletin, May 20, 1866, printed the following: "By mutual consent, the undersigned withdraws from the firm of A. RUTTKAY & CO., in which Firm he was heretofore a partner." The signatory below is identified as C. B. Zulavsky and the notice attests that it was made on May 10, 1866, in Galveston, Texas. None of the newspapers in Galveston, Houston or Dallas contained stories about the dissolution or offered reasons for it.

Albert Ruttkay was also instrumental in introducing his younger brother Gabriel into the cotton trade. Sadly, Gabriel perished when the Varuna foundered off the Florida coast while on its way from New York to Galveston in November 1870. The tragedy, triggered by powerful gales, was covered in the principal papers of the nation since nearly two dozen prominent citizens of Galveston died in the sinking of the vessel. The New York Times, November 11, which listed the victims, denoted Gabriel as Ruttkey and described him as "an estimable young merchant of less than thirty years. He was until recently, and we presume at the time of his death, with the house of DUNCAN & SHERMAN. His mother was a lady of remarkable character, and took an active part in the political affairs of Hungary. Gen. Kossuth, the Hungarian patriot, was an uncle to Mr. RUTTKEY." Lujza was utterly devastated by the loss of her youngest son.

Albert Ruttkay died at his residence on November 13, 1888, after a protracted illness. Presenting some personal facts about him and the pending funeral, the obituary notice in the Galveston Daily News added that "During his few years' residence in this city, by his strict business integrity, noble traits of character and general disposition, he commanded commended the respect and friendship of a large circle of warm and true friends."

Like Albert Ruttkay, Ladislas Zulavsky took up the cotton trade after the war, setting up business in Augusta, Georgia. According to the local papers, he enjoyed considerable respect for his integrity and other personal traits. For a while his enterprise thrived. When his affairs encountered reverses, the stress and strain he experienced led to his mental breakdown. He was taken back to New York and committed to the asylum at Middletown. The tragic deterioration of his mental health was reported tactfully and sympathetically in a number of newspapers, e.g. The Atlanta Constitution, November 9, 1883. Ladislas remained institutionalized until his death which occurred on April 22, 1884; he was but 47 years old.

After terminating the partnership with Albert Ruttkay, Casimir Zulavsky vanished into obscurity. Even more puzzling is the fate of his brother Emil. No researcher has reported any definitive facts about his post-Civil War fate. Albert Ruttkay's obituary in the November 13, 1888, edition of the Galveston Daily News referred to him as "the sole surviving nephew of Kossuth," implying that Emil and Casimir Zulavsky had died prior to this date. Whether this is accurate or not remains a moot point. Concrete facts about both Casimir and Emil would be most welcome.

In 1881 Lujza Ruttkay left the United States to join her illustrious brother, now long a resident of Turin, Italy. The vast distance notwithstanding, she didn't break off contacts with friends and relatives in America; on the contrary, she maintained a brisk correspondence with loved ones. The chapter entitled "At the Seminary" in Scenes and Portraits by the renowned literary historian and novelist Van Wyck Brooks vividly recounts Lujza's life with Kossuth until his death.

The death of the revered patriot in1894 at the age of 92 attracted worldwide media coverage. Hungarians in the United States held memorial services; particularly imposing and elaborate services were held in New York City. Among many attendees, which included many Americans harboring fond recollections of Kossuth, were members of the Zulavsky and Ruttkay families. While the only notable representative of the Zulavsky family at these functions was Ladislas' widow, the Ruttkays, led by Albert Ruttkay's widow Laura, were more numerous.

The occasion unleashed a flood of articles about Kossuth in the American media, naturally reminiscing about his tour of the United States and his moving and inspiring speeches. The saga of his sisters wasn't neglected either; a particularly interesting and valuable article was penned by Louis Ruttkay, son of Albert and Laura, for the New York Herald Tribune, April 16, 1894. While it provides ample details on Lujza Ruttkay and her three sons and their descendants, the discourse on the four Zulavsky brothers is sparse and vague. This seems to indicate that the Ruttkay family didn't maintain ties with Emil and Casimir Zulavsky after the Civil War.

Following the death of her brother, Lujza returned to Hungary permanently. Enjoying universal public esteem as one of the few living links to the great patriot, she died in 1902. All the leading American papers printed her obituary, varying from succinct perfunctory notices to lengthy reviews of her life.

Notes and additional comments:

The circumstances prompting the departure of the three Kossuth sisters and their families from Hungary as well as their voyage to America and their arrival are recounted in considerable detail in the sundry documents compiled by Dénes Jánossy in A Kossuth-emigráció Angliában és Amerikában, 1851-1852 [The Kossuth Emigration in England and America], published by the Hungarian Historical Society in 1948. The memoirs of several exiles, notably those of Károly László and the Reverend Gedeon Ács, contain interesting odds-and-ends about the three sisters and their children during the 1850s.

There is an array of books in Hungarian, Italian and English about the Hungarian Legion in Italy. Arguably the most scholarly and comprehensive of these and also giving the most information about Ladislas and Emil Zulavsky is Lajos Lukács' Az olaszországi magyar légió története és anyakönyvei, 1860-1867 [The History of the Hungarian Legion in Italy and Biographical Sketches, 1860-1867], published in 1986.

The Civil War careers of the Zulavsky brothers and Albert Ruttkay are more than amply recounted in the documents held at the National Archives and Records Service as well as in a host of standard reference books concerning the war.

In deference to his father's ethnicity, Ladislas Zulavsky appears in a number of Polish-American books and journals. The information presented in these publications on the Zulavsky family was invariably gleaned from Hungarian or American sources, often carelessly, resulting in a number of glaring errors.

Albert Ruttkay's post-Civil War years are covered in James Patrick McGuire's The Hungarian Texans (1993). This book also mentions Casimir Zulavsky and his misdeeds.

The treatise in Van Wyck Brooks' book is based on some 70 letters written by Lujza to Eliza Kenyon, a dear friend living in Plainfield, New Jersey. A very cultured lady like Lujza, Miss Kenyon was a relative of Brooks' wife. Brooks encountered these letters while sorting out her effects after her death. There are some minor factual errors in the account due to Brooks' lack of first hand familiarity with the Kossuth sisters and their families. |