Some Reminiscences about Lajos Zilahy

|

In 1938 Zilahy founded Pegazus, a company for the production of motion pictures. He not only adapted several of his novels and plays to the screen but also directed the filming, becoming a complete auteur. It is often forgotten that he was an outstanding journalist as well. His most notable activities in this field were his editorship of the daily paper Magyarország [Hungary] from 1934 to 1936 and his editing of the Híd [Bridge], a literary periodical, from 1940 to 1944. His works were written from a literary, political, and social viewpoint and he always strove to capture the timeless aspects of human existence. Panoramic action, richness in characters, vivid style, pageantry, humor, and erudition are just a few of the attributes credited to his prolific output. A New York Times article once remarked that Zilahy is “one who believes that the writing profession is noble and that the mission of those devoted thereto is to do good.” Given Zilahy’s prominence, it is surprising that no comprehensive book detailing his life and accomplishments has been written. Mária Ruzitska’s Zilahy Lajos, published in 1928, covers only the beginning of his career. Zilahy Lajos utolsó évei [Lajos Zilahy’s Final Years] by János Siklós in 1986 is derived from a series of rambling newspaper articles dating from prior years. A number of reference texts, such as Joseph Remenyi’s Hungarian Writers and Literature (1964), Albert Tezla’s Hungarian Authors - A Bibliographical Handbook, and Lorant Czigany’s The Oxford History of Hungarian Literature (1984), contain substantial sections on Zilahy, but with a focus on his principal works. The participation of his wife Piroska in the oral history project concerning Lajos at Columbia University in 1977 - a veritable gold mine of information on his private and professional life - won’t be available to the public until 2015 in deference to the 10-year closure after death of the interviewee policy. Considering that Zilahy’s long life spanned some of the most turbulent and tragic years in Hungarian history, the broad spectrum and sheer volume of his literary output, and his role as a public figure, it would certainly be a most formidable task to write an accurate, fair, and detailed biography.

It is not my intention to provide profound insights into his life, to debate the literary merits of his works, or to dwell on his political views. I would just like to comment on some little known aspects of his life and accomplishments. I had the opportunity to meet him many times because my paternal grandmother was his younger sister Ilona, or Ica as he was fond of calling her. By the way, one of Zilahy’s most enduring novels, Two Prisoners, is the fictionalized story of my grandparents around the time of World War I. The book has also been turned into a film, with Pál Jávor and Gizi Bajor, two of the premier figures of the Hungarian cinema of the 1930s, in the leading roles.

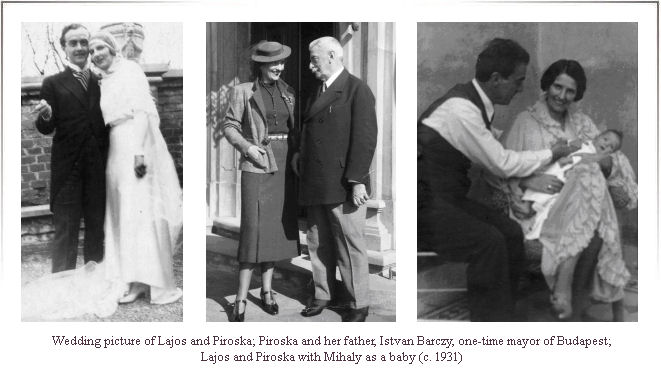

I was also fortunate to meet several of Zilahy’s artistic collaborators. The cinematographer Árpád Makkay was a frequent guest at our home in New York, and later in Toronto I socialized often with the composer Tibor Polgár and his wife Ilona Nagykovácsi, the famous singer. Once in the early 1960s I fielded a telephone call from none other than Katalin Karády, the beautiful star of numerous Hungarian movies of the ’30s and ’40s, but by then even more of a recluse than the legendary Greta Garbo. They are all gone, but their legacy lives on. It is true: life may be short but art is long. My earliest vivid recollection of Lajos dates from a warm autumn evening in New York in 1957 shortly after my mother and I arrived from Europe. Lajos, my father and I were standing on the corner of 79th Street and First Avenue near a newsstand (which, by the way, is still there). At one point, Lajos made some comment about the financial rewards of the literary profession. Deeply immersed in the reading of comic books which were not only highly entertaining but also an excellent means of learning English, I assured him, with all the confidence of an 11-year old, that the future of literature lay in the writing of comic books. He didn’t answer me; he just gave me a blank look that spoke volumes. When Zilahy was born at Nagyszalonta in 1891 Hungary was part of the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary. His father was a notary public and his mother was the daughter of a landowner. He was not the scion of privileged classes as some American biographical accounts insinuate. Following studies at local schools, he obtained a doctorate in jurisprudence from the University of Budapest. He experienced all the horrors of World War I, and subsequently witnessed the dismemberment of Hungary by the victorious Allied powers in order to reward their client states. He also endured the short-lived reign of terror of Bela Kun and his Bolshevik-inspired cronies. A slim volumes of pacifist poems published in 1916 brought Zilahy his first literary recognition. Abandoning the legal profession, he devoted all his time to writing and became famous with Halálos tavasz [Deadly Spring], a pessimistic and tragic love story, in 1922. The release of Two Prisoners in 1927 propelled him to international fame. Incidentally, several of Lajos’s writings were inspired by family members or incidents involving relatives. As mentioned, Two Prisoners was based on the events which befell his sister and her husband. My father told me that the protagonist of A lélek kialszik [The Soul Extinguished] - a young man who leaves Hungary to seek his fortune abroad - was modeled on his uncle Dezső Beszedits. A few years older than my grandfather, Dezső emigrated shortly before World War I. In the ensuing years he wrote sporadically from the United States, Brazil and Mexico. My father never ceased to wonder about the life he led and his ultimate fate. The answers remained a mystery until a few years ago when I received an E-mail from Brazil from an Alexandre Beszedits, a grandson of Dezső. After we initiated a steady correspondence, I learned all the details about Dezső, who certainly merits to be described as a colorful spirit and whose adventurous real life story easily surpasses that of Lajos’s fictional character. The excellence and popular appeal of Zilahy’s writings led to his election to several literary and cultural societies, among them the Kisfaludy Társaság in 1925. The following year he served as president of PEN Club. In 1930 Zilahy married Piroska Bárczy, daughter of István Bárczy, a former mayor of Budapest. Their only child, a son, Mihály was born in 1931.  The 1930s were one of the most unsettled and violent decades in recent history. The worldwide depression, international rivalries, aggressive expansion by dictatorial and totalitarian regimes, and the rise of the unholy trio of isms: Fascism, Nazism and Communisms created a tense political atmosphere throughout Europe. Even the United States, still pursuing a more or less isolationist policy, wasn’t immune to the ill winds. In a letter to Franklin Delano Roosevelt, dated October 5, 1935, the Reverend Joseph Matuskovits, pastor of New York City’s Hungarian Baptist church, congratulated the President for the passing of the Social Security Law, advanced a number of suggestions to alleviate the plight of the legions of unemployed, and reflected sadly on the gains by Fascist, Nazi and Communist propaganda in the neighborhood.

There were even Americans, individuals of sound mind and good education, who flocked to the Soviet Union, and blissfully ignoring the genocides, deportations, purges, show trials, mass executions, and other unsavory, undemocratic and inhuman policies of the government proclaimed Stalin as the new Messiah. How people can be overcome by such delusion is one of the great puzzles of the ages. Perhaps television’s Dr. Phil, who has provided insight into many revolting perversions, can offer some answers. With the publication of A szökevény [The Deserter] in 1930 which was followed by a number of equally acclaimed novels and plays, Zilahy’s reputation grew by leaps and bounds. Many of his writings from this time contain eloquent pleas for world peace. As a prominent public figure, he stressed moderation and a genuine concern for social reform. Said Emil Lengyel in a New York Times article on September 4, 1938: “He is one of those champions of the new day who have the courage to proclaim their faith in sanity.” In 1942 Zilahy bequeathed a small fortune to the nation for the establishment of an elitist college, i.e. Kitűnőek Iskolája. His avowed purpose for setting up the institute was noted by the press throughout the world. In September 1942 an unexpected Russian air raid destroyed Zilahy’s house on the Rózsadomb in Budapest. Fortunately for him and his family they were away on that fateful day. Zilahy’s opposition to the war, his revulsion toward fascism, and the banning of his play Fatornyok [Tree Tower], replete with messages not in favor with the politicians in power, in 1944 are all well-known. While Zilahy along with his wife and son managed to survive the war, including the siege of Budapest which left much of the city in rubble, his beloved sister Ilona was among the casualties as she was killed in a crossfire during the vicious house-to-house fighting.

The end of World War II did not end the sufferings for Hungary. On the contrary, the nation was about to experience the darkest years in its history. For his help in defeating Hitler, the grateful Western powers gave Stalin a free hand in Eastern Europe - undoubtedly the greatest crime ever perpetrated against humanity. Trailing on the heels of the “liberating” Red Army were the sycophantic Mátyás Rákosi and his stooges - After living in Brooklyn for a while, Zilahy moved to a brownstone on the north side of 82nd Street, close to First Avenue, in the Yorkville district of Manhattan. In those days the neighborhood was distinctly ethnic, German, Czech, and of course Hungarian. An article in The New Yorker, May 21, 1949, referred to him as “a genial, slow-spoken, clean-shaven, bifocaled man of fifty-eight” who “likes nearly everything he has seen in America except the loud, verticillate neckties now in vogue.” On November 28, 1949, Lajos and Piroska were stunned to learn that their son had been the victim of a fatal accident. The tragedy occurred as Mihály, a freshman at Harvard University, was trying out for the school’s rifle team. According to the New York Times’ report of the incident, the weapon discharged as he was adjusting the strap of his rifle. The bullet Piroska often said that she did not believe in venerating the dead. Yet she never ceased to perpetuate Lajos’s memory and always did her utmost to promote his works. The Dukays (1949), regarded by certain American critics as one of his most accomplished works, ignited considerable controversy. It made the best sellers’ list, but its subject matter invoked a lot of displeasure against its author. Nevertheless, Zilahy’s literary reputation remained unscathed. Proclaimed the dust jacket of his Century in Scarlet, published by McGraw-Hill,: “Lajos Zilahy is generally regarded as the most distinguished living Hungarian writer.” The dust jacket of The Angry Angel, from Prentice-Hall, declared that the book “will be an especially rich and rewarding experience for those who will meet for the first time the magnificence, the wit, the excitement, the insight and the pure entertainment of the famous Zilahy style.” The Penguin Companion to European Literature (1969) commented that “of living Hungarian authors his works are the best known in the West.” These literary triumphs did not translate into hefty financial gains and hence Lajos and Piroska lived under modest circumstances. They also spent much of their time in Rhode Island. While Lajos wrote Piroska worked at one of the local hospitals. Incidentally, according to one family story, Zilahy was able to salvage only a small portion of his wealth from Hungary, mostly in British pounds which later turned out to be counterfeit. Hungarian publications about him under the Communist regime were always obliged to follow party directives. Thus his brief entry in the Új magyar lexikon (1961) concludes with the following: “Az USA-ban él és a Magyar Népköztársasággal szemben ellenséges tevékenységeket folytat” [He lives in the USA and is engaged in hostile activities against the Hungarian People’s Republic]. Which is typical of the lunatic ravings emanating from Communists. Despite the proliferation of such preposterous babble from the demigods of the workers’ and peasants’ paradise, his A szűz és a gödölye [The Virgin and the Fawn], one of his endearing creations, was revived by the Jókai Színház in Budapest in 1957. Despite his literary triumphs, Zilahy began to fade from the public eye. Even most Hungarian-Americans residing in New York City were unaware of his presence in the mid-1960s. I remember that when as a freshman at Columbia University I mentioned that I was related to Zilahy to one of my Hungarian professors he was very much surprised to hear that Lajos was still among the living. Even after celebrating his 80th birthday, Zilahy remained active, vigorous and restless, always seeking new projects. Because he had money from royalties in Spain and Yugoslavia, he decided to remake Deadly Spring, setting it in these two countries (as opposed to Budapest and the countryside in the original version). With a cast of largely unknown performers the script was indeed filmed. The musical score was composed by Tibor Polgár who spent several weeks with his wife on location in Spain. Upon their return to Toronto, Tibor and Ilona had lots of anecdotes about Lajos and the movie. Not long afterwards Zilahy died unexpectedly. According to Tibor and Ilona, the film became lost due to Lajos’s passing and the political and social turmoil in Spain and Yugoslavia following the death of Franco and Tito. Death overtook Zilahy at Újvidék on December 1, 1974. His body was cremated and his ashes were laid to rest at the Farkasréti Cemetery in Budapest. His obituary in the New York Times, December 3, 1974, was cursory; it dwelt mostly on his works written and/or performed in the United States. A number of Hungarian writings following his death claimed that he intended to return permanently to Hungary. According to Piroska, while Lajos indeed contemplated returning, he remained steadfastly ambivalent about it. Piroska survived Lajos by three decades and passed away in 2005. She spent most of the intervening years coping with deteriorating health and declining financial resources in Rhode Island. But she never complained and bore her fate with equanimity and dignity. Fortunately and importantly, she enjoyed the unflagging support of a large circle of local Zilahy admirers. The innumerable biographical sketches of Zilahy in Hungarian, English, and many other languages invariably concentrate on his major novels and most popular films. His numerous plays are usually glossed over and their production outside Hungary rarely touched upon. The three plays which made Zilahy a familiar figure to American theatre goers were: Szibéria [Siberia], A tábornok [The General], and Tűzmadár [Firebird]. The Budapest presentation of Siberia - a play revolving around a group of Hungarian prisoners-of-war in Russia during World War I - didn’t go unnoticed abroad; the New York Times of April 15, 1928, commented that “A quantity of well-done detail always make Zilahy’s stage work enjoyable.” The melodrama was brought to the United States by Lee Shubert. At the time, the Shubert brothers, Lee and Jacob J., were the nation’s most important and powerful theatre owners and managers and they also built many of the famous theatres lining Broadway. With the adaptation by William A. Drake and the title changed to In Command, the play was advertised in the papers as a “beauteous and unparalleled love epic,” and a “dramatic masterpiece that requires no superlatives to acclaim its greatness.” The star of the play was Richard Bennett, one of the outstanding actors and matinee idols of his time. Bennett was an irascible, boisterous and self-centered individual whose performances were often gently mocked as the “Bennett artistry.” The New York Times critic of the play on March 9, 1930, assured the readers that “the paying customers who, after the play, can conscientiously contend that Mr. Bennett is not “the dominant figure” will probably get their money back at the box office.” Also set in Russia, A tábornok [The General] had a plot which could be succinctly summarized as a “dramatic love narration of intimacies in the lives of three leading characters, constituting an unusual treatment of the eternal triangle theme.” The success of the play in Hungary and elsewhere in Europe induced Paramount to acquire the motion picture rights to it. In January 1930 Zilahy traveled to Hollywood to oversee the adaptation and filming of the story. The adaptation was done by Martin Brown, himself a distinguished playwright. The co-directors were George Cukor and Louis Gasnier; the latter chiefly remembered for the 1936 cult film Reefer Madness. Released as The Virtuous Sin, the movie was accorded uniformly favorable reviews, with the performances of the two leading players, Walter Huston and Kay Francis, getting the lion’s share of the praise. Said the critic for the Hartford Courant, October 25, 1930: ”Miss Francis is splendidly adequate and portrays her part with a finesse and depth” and “Walter Huston scores another distinctive character study.” Although she wasn’t top billed, Kay Francis appeared in almost every scene and the picture offered the rare opportunity to hear her sing in her own voice. The New York Times, of the same date, concluded that: “Undoubtedly a great deal of its success is to be attributed to the clever script written by Martin Brown.” However, the Zilahy play that drew the most attention abroad was Firebird. The plot basically concerned a murder and a cover up involving a married woman with a 16-year old daughter who is finally revealed as both the lover and the killer of the dead man. The play also touched upon mother-daughter relationship along with the problems confronting rebellious post-war youth. Following a highly successful run in Budapest, producer Gilbert Miller decided to present it on Broadway in the fall of 1932. He engaged British dramatist Jeffrey Dell to carry out the adaptation and secured the distinguished Judith Anderson for the lead role. Other prominent cast members included Henry Stephenson, Ian Keith, Montagu Love, and Nita Naldi. Miller, who was an active and important theatre figure not only in New York but also in London, announced that he would bring the play to the British stage as well. For this production, the renowned Gladys Cooper was retained for the lead role, while her husband Zilahy himself arrived in New York aboard the trans-Atlantic liner Majestic on November 8, 1932. Reflecting on the grave economic conditions and tense political situation prevailing in Europe, he said: “We must fight against the exaggeration of nationalities. We must help each other. But I am a nationalist, too, in regarding Hungary as the most unfortunate nation of Europe. It is only that I know the good future of all Europe means the good future of my own country.” While the New York production of Firebird was in preparation, the British version of the play made its debut at the Playhouse, a theatre with a rather modest seating capacity of less than 700. It was greeted with ecstatic reviews and the overwhelming majority of the newspapers declared that the playhouse has another smash hit on its hand. Over 120 performances were given and 30 more on the road. Concerning this production, critic Charles Morgan, in an article titled “As a Theatre Piece “Firebird” Scores in London,” appearing in the New York Times on September 25, 1932, judged the play to be “admirably constructed, its secrets are skillfully inverted and preserved, its denouement is quick and vigorous, and the behavior of its people is steadily and adequately accounted for [...] Smooth and shapely, it is as well contrived a piece for the theatre as has been seen in London for some time.” As for the players, Mr. Morgan singled out Antoinette Cellier, a young and unknown actress, for her bravura performance as the daughter. Firebird’s American debut was on November 21, 1932, at the glittering Empire Theatre. With just over 1,000 seats, it was a compact, well-designed playhouse and a favorite among actors and audiences. The audience that night, remarked one newspaper, “was fully as fashionable as the one attending the opera across the street.” On the following day, the critic for the New York Times opined that “despite the attention it has received and the even competence of the writing and construction, “Firebird” is nothing sensational in the line of mystery murder plays. Nor does it attempt to be. It is extremely well-bred and deliberate in movement.” Critic Richard Dana Skinner in the December 7, 1932, edition of the Commonweal praised the excellent production values and the superb cast, giving particular recognition to Elizabeth Young “whose playing of the distracted daughter ranks among the exceptional individual performances on Broadway this season.” But he was less enthusiastic about the play itself, saying that “it is unfortunate that Mr. Zilahy could not have made the most of his interesting theme, and have abandoned the attempt to write a clever mystery for the greater chance of writing a fine play.” According to the Catholic World, January 1933, “Mr. Zilahy, the Hungarian playwright, had the chance of a mystery or a problem play and has chosen to combine them. The result is two acts of each, and each half excellent in itself though forming an imperfect whole.” While the New York staging reviews were lukewarm at best, the critical opinion on the European performances remained very much on the positive side. Critic C. Hooper Trask was deeply impressed by the Berlin production of the play. Reviewing it in the New York Times, December 18, 1932, he described the plot as “waterproof, watertight, all wool, three-ply - all the things demanded by the best ready-made dramatic tailoring.” And added that “the dramatic line rises straight to the final curtain and the characters are sketched in with taste.” Zilahy lived a long and fruitful life, shaped to a large extent by the prevailing currents of history. Many things can be said about him, but one fact cannot be disputed: his place among the literary giants is secure. Time has neither diminished nor tarnished the significance and appeal of his works. Future generations will continue to enjoy his novels, short stories, plays, and films. |

|

Stephen Beszedits

s.beszedits@utoronto.ca |