|

Who was this man, this Joseph Pulitzer, this transforming giant of American journalism and founder of the famous Pulitzer Prizes? What made him tick? The story begins, improbably, in Makó, Hungary, where Pulitzer was born in 1847.

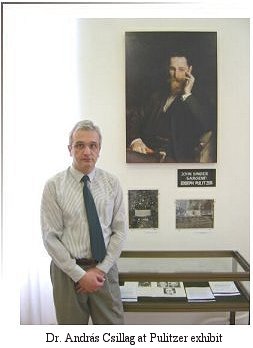

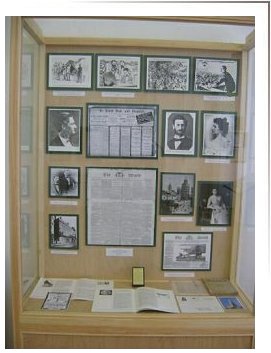

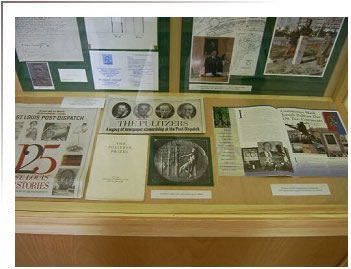

To tell that story and bust some myths, the Makó historical museum has mounted an exhibit on Pulitzer and his family which is now  on view, through June 30, [2004], at the larger Móra Ferenc Museum in Szeged. Among the wealth of articles on display are Hungarian birth and tax registers dating back to the 1700s. There is a letter in Gothic German script, written in 1855, attesting to the impeccable character of Pulitzer's father Philip. And there is a photo of the old stone house in which Pulitzer was born, across the street from Makó Town Hall. Many of these items bear directly on disputed aspects of Pulitzer's biography, and the man who unearthed and put them there - Dr. András Csillag, a historian at the University of Szeged and author of Joseph Pulitzer and the American Press - is a man with a mission. He wants to remind the world of Pulitzer's accomplishments and Hungarian origins, but he also wants to correct what he perceives as egregious errors in previous accounts of Pulitzer's life. on view, through June 30, [2004], at the larger Móra Ferenc Museum in Szeged. Among the wealth of articles on display are Hungarian birth and tax registers dating back to the 1700s. There is a letter in Gothic German script, written in 1855, attesting to the impeccable character of Pulitzer's father Philip. And there is a photo of the old stone house in which Pulitzer was born, across the street from Makó Town Hall. Many of these items bear directly on disputed aspects of Pulitzer's biography, and the man who unearthed and put them there - Dr. András Csillag, a historian at the University of Szeged and author of Joseph Pulitzer and the American Press - is a man with a mission. He wants to remind the world of Pulitzer's accomplishments and Hungarian origins, but he also wants to correct what he perceives as egregious errors in previous accounts of Pulitzer's life.

The broad contours of that life are well known and not contested. In 1864, when Pulitzer was 17, he traveled from Hungary to New York City, where he enlisted in the Union Army for the last year of the American Civil War. After the war he made his way to Missouri, where he became a journalist and founded the St Louis Post-Dispatch. With that newspaper and two others in New York, the World and the Evening World, he engineered what can only be called a revolution in American journalism. His guiding principle was the notion that a rigorous free press is indispensable to political freedom and democracy. "Our Republic and its press," he wrote in 1904, "will rise or fall together." He committed his papers to the interests of working people and spared no effort in exposing corruption in government and business. He perfected the art of investigative reporting, added cartoons and  illustrations to his news columns, and agitated for popular reforms like taxes on inherited wealth and anti-trust laws. Pulitzer's support for Grover Cleveland, the Democratic presidential candidate in 1884, was crucial to Cleveland's election. The following year, Pulitzer used his power and influence to raise the funds needed to build a pedestal for the Statue of Liberty. Prior to his death in 1911, he endowed a school of journalism at Columbia University and established the annual Pulitzer Prizes. These are the facts, among many others, which aren't in dispute. illustrations to his news columns, and agitated for popular reforms like taxes on inherited wealth and anti-trust laws. Pulitzer's support for Grover Cleveland, the Democratic presidential candidate in 1884, was crucial to Cleveland's election. The following year, Pulitzer used his power and influence to raise the funds needed to build a pedestal for the Statue of Liberty. Prior to his death in 1911, he endowed a school of journalism at Columbia University and established the annual Pulitzer Prizes. These are the facts, among many others, which aren't in dispute.

What galls Dr. Csillag are the myths about Pulitzer that stubbornly persist even in the writing of such distinguished observers as Seymour Topping, a former New York Times reporter, who authored the sketch of Pulitzer's life for the web site of the Pulitzer Prize Board in New York. Perhaps the most troubling of those myths, in Csillag's view, concerns the heritage of Pulitzer's mother, Elize Berger. Topping notes in his sketch, consistent with other biographers, that while Pulitzer's father Philip was "a wealthy grain merchant of Magyar-Jewish origin," his mother was a "German" and "a devout Roman Catholic.” Topping adds that Pulitzer's younger brother Albert "was trained for the priesthood but never attained it.” "Absolute nonsense," Csillag declares. "Elize Berger was a Hungarian Jew from the large Jewish community in Pest," the capital of Hungary now called Budapest. This is proven, he says, by a cascade of archival documents in Makó, including "the popular conscription"-or census-of 1850 and "passports for travel out of the city.” Not a few of those documents are naturally on display at the  exhibit in Szeged. Why should we care about the ethnicity of Pulitzer's mother? "The fact," says Csillag, "that both Pulitzer's parents were Hungarian Jews made Joseph himself a Hungarian Jew, not half-German Catholic. Jews in Hungary in the 19th century - as a class, as an ethnic minority - were discriminated against, sometimes severely. This could help explain Pulitzer's instinct later in life, when he became a journalist, to identify with the disenfranchised in America, to defend the interests of the poor and oppressed." exhibit in Szeged. Why should we care about the ethnicity of Pulitzer's mother? "The fact," says Csillag, "that both Pulitzer's parents were Hungarian Jews made Joseph himself a Hungarian Jew, not half-German Catholic. Jews in Hungary in the 19th century - as a class, as an ethnic minority - were discriminated against, sometimes severely. This could help explain Pulitzer's instinct later in life, when he became a journalist, to identify with the disenfranchised in America, to defend the interests of the poor and oppressed."

A second important myth about Pulitzer, "or rather perhaps misconception," says Csillag, has to do with "the revolutionary impulse and taste for democracy" that Pulitzer brought to his newspapers. Tradition holds that those attributes were passed on to Pulitzer by Carl Schurz, publisher of the German-language Westliche Post in St. Louis, where Pulitzer started his career as a journalist. "That is plausible," says Csillag, because Schurz, a former general in the Union Army, "was a bonafide radical who had fought in the German revolution of 1848." But Csillag doubts that Schurz was responsible, per se, for Pulitzer's intense devotion to democracy. "At most,” he contends, “Pulitzer found in Schurz a revolutionary spirit that matched his own.” Indeed, Hungary had experienced a revolution in 1848, one year after Pulitzer's birth - a popular revolt against the ruling Habsburg monarchy in  Austria - that was more successful and lasted longer, until August 1849, than any other of the 1848 revolts in Europe. "Pulitzer's father Philip," says Csillag," was appointed a food supplier to the rebel army by Lajos Kossuth, the leader of the revolution. He received a signed document from Kossuth to that effect. And two of Pulitzer's uncles were soldiers in the revolution." Austria - that was more successful and lasted longer, until August 1849, than any other of the 1848 revolts in Europe. "Pulitzer's father Philip," says Csillag," was appointed a food supplier to the rebel army by Lajos Kossuth, the leader of the revolution. He received a signed document from Kossuth to that effect. And two of Pulitzer's uncles were soldiers in the revolution."

It is inconceivable, says Csillag, that Joseph Pulitzer wouldn't have inherited his "revolutionary impulse" from those family members and other Hungarian radicals around him in his youth. As if to demonstrate that in 1894, when Kossuth died in exile in Italy, Pulitzer published an obituary in his New York World that "was utterly effusive in its admiration for the man. It spoke above all to his merits as a revolutionary leader and statesman." Moreover, says Csillag, "Pulitzer assigned a special correspondent to cover not only Kossuth's funeral but the progress of the funeral train from Turin to Budapest. And he ordered a wreath of flowers for his grave.

|